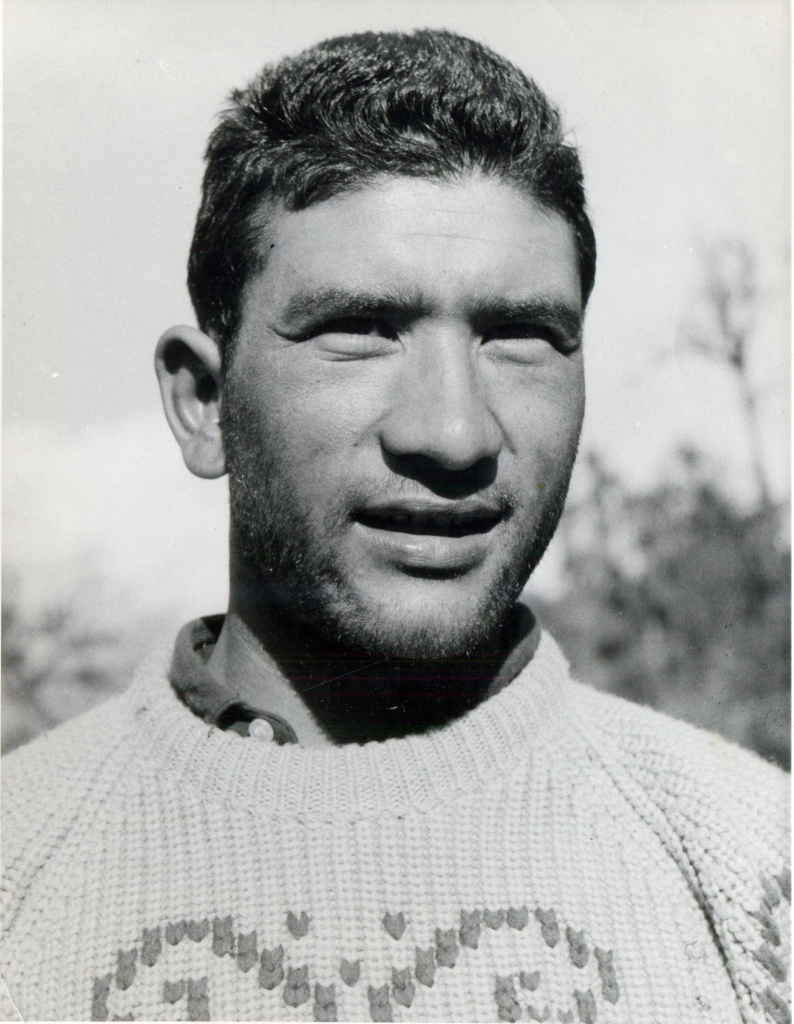

From humble beginnings in Leh, Sonam Wangyal became a legend in the mountaineering world as the youngest to climb Everest in 1965

First published: https://www.firstpost.com/india/among-first-indians-to-summit-mount-everest-sonam-wangyal-recounts-fabled-1965-expedition-on-its-anniversary-8386501.html

Among first Indians to summit Everest, Sonam Wangyal recounts fabled 1965 expedition

During the school assembly one morning in 1953, an announcement made by the headmaster snapped 12-year-old Sonam Wangyal out of his reverie: Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary had touched the sky by making the first successful climb to the summit of Mount Everest. For the next few days, Wangyal would wake up in the wee hours of the morning before school and from under the comfort of his blanket, look out of the window in earnest.

“I thought that if they could ‘touch the sky’ from the top of Everest, surely this was a mountain that could be seen from my home in Leh,” Wangyal says, chuckling.

The epic first in mountaineering history had set his mind racing. But never would Wangyal have imagined that just 12 years later in 1965, he would be among the first Indians to stand atop Everest. It’s been 55 years to that day in May and Wangyal admits that life would have been very different if it wasn’t for a few chance moments that came his way.

“My mother passed away when I was just eight and my father was always on the move due to work. I didn’t have anyone to back me, so I had to work hard for everything that I have achieved,” he says.

Though the dusty, russet mountains of the Ladakh range had always been in his backyard, Wangyal took up more conventional sports at school and excelled at most of them. From shot put, long jump, high jump and sprints, to playing football, hockey, polo and volleyball, he was a routine feature on most playgrounds, an all-rounder, who preferred play over books.

“I don’t know how many fingers I must have broken on the volleyball court,” he laughs.

After finishing the matriculation examination, Wangyal joined what is now known as the Indo Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) as a sepoy. The teenager got his first experience of combat during a border skirmish with the Chinese near Chushul in 1959. The opportunity to climb arrived the following year when he was drafted on a team to climb Stok Kangri — a 6,153 metre-peak overlooking the city of Leh.

“I never thought I would get to the top because a lot of Britishers had attempted it and had been unsuccessful. Besides, I didn’t know how to tie a rope or put on a crampon,” Wangyal recalls.

On the final push to the summit, he put himself between two experienced climbers and maintained pace. The light was fading and Wangyal wondered how they would survive the night without food or adequate clothing. By the time they got to the top, it was pitch dark. With handheld torches at their disposal, they realised that descending on all fours would be a risky proposition and stayed put a little below the summit.

“It was October, really cold and we had to massage and slap each other to keep the circulation going,” he says.

That first climb led to 22 other successes on Stok Kangri, besides other mountains such as Hathi Parbat in Uttarakhand. In September 1964, he received a letter from the Indian Mountaineering Foundation that would change his fortunes. It had taken a month for it to travel from New Delhi to the remote village of Hundar in Nubra Valley where he was posted as an instructor.

“For a havaldar to receive a note from the deputy secretary of the Ministry of Defence was huge. I had been asked to join a pre-Everest expedition in Darjeeling that was to attempt Rathong peak as part of the selection,” he says.

By then, only two other parties had made it to the top of Everest — the Swiss in 1956 and the Americans in 1963. India had made two unsuccessful attempts in 1960 and 1962, and a lot was at stake on the third attempt led by MS Kohli. The climb up Rathong (6,678m) was a success, as Wangyal was part of the first summit party. Soon, he found himself on the Everest team scheduled for the spring of 1965.

“I spent a lot of time training on the mountains around Leh after my selection,” he says.

The team assembled in New Delhi in February and after a sendoff by then prime minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, set off for the border at Jaynagar in Bihar. It took close to a month for the team to finally establish base camp under the shadow of Everest. On the march in, Wangyal realised that he was the youngest on the team and among the more inexperienced members.

“The others were all at higher posts, while I was just a havaldar. So I felt a little uneasy at the start. I was most comfortable with the Sherpas, since their eating habits were similar to us Ladakhis. Since I was young, they loved me like a kid and treated me as their little brother. I ferried loads with them and opened up the route till 26,000 feet,” Wangyal says.

During those early days, Wangyal left a good impression on his teammates. In his book, Nine Atop Everest, Kohli, the leader of the expedition, writes:

‘This well-built mountaineer has muscles of steel. His remarkable physical prowess impressed everyone. The high altitude, physical privations, winds and temperature never made any dent on his mind or body. A very competent climber, he was remarkably calm, of equable temper and thoroughly trustworthy. He was utterly selfless, sincere and a loyal teammate. He could be entrusted with the most difficult task and he would accomplish it without the least murmur. Good at heart and ingenuous, he was always on his toes.’

By 19 April, the camps had been established on the mountain and the team descended to base camp to rest before the final summit push. Wangyal had been paired with Sonam Gyatso — one of the most accomplished Indian mountaineers, who had been a member of the teams that had climbed Cho Oyu in 1958 and made the first ascent of Annapurna III in 1961, as well as the two previous Everest expeditions. However, at 42, he was the oldest among the climbers, and was now teamed up on the climb with the youngest and his namesake, Wangyal.

As early as 27 April, the first summit party featuring AS Cheema, Nawang Gombu and the two Sonams sat in at South Col, hoping to go for the summit. But with bad weather predicted during the days ahead, they were asked to make a quick retreat to recuperate at base camp.

It wasn’t until 14 May that they received reports of calm weather from the meteorological department. Kohli was aware that given how late it was in the season, they were now looking at one final attempt on the mountain. The pressure was palpable as Cheema and Gombu started off, setting up summit camp above South Col by 19 May. The following day, they were the first Indians to get to the top of Everest.

On their descent, they met Wangyal and his partner, who were now on their way up to South Col. The following day, high winds and snowfall pounded the climbers, as they struggled to locate the buried tents at summit camp.

“The winds were around 130 kmph and I thought I would be carried away with the tent. Gyatso had developed a deep gash on his hip. I too had frostbitten toes since some snow had entered my shoes. There were doubts about whether we could continue to the summit. Since we were both mountain lovers (Gyatso was from Sikkim), we arrived at the decision to go on,” Wangyal says.

That night, Wangyal did everything that he could to comfort his partner — from letting him use the oxygen, to taking on the tedious task of melting snow and brewing tea at that altitude. The weather abated the following morning as they set out for the top. At 12.30pm on 22 May, the duo met success — Wangyal the youngest at 23 and Gyatso the oldest at 42 to get to the top of Everest.

“We put up flags and took a few photos. It was only after reaching base camp that we realised that the camera roll had not been loaded properly. After 55 minutes on the summit, we started our journey down,” Wangyal says.

However on reaching the Hillary Step — it is a vertical rock feature at 8,790m — on the descent, Wangyal realised that he had forgotten to place the idol of Lord Ganesh on the summit, which had been given to him by BN Mullick, a senior official of the Intelligence Bureau.

“I owed him a lot, so I decided to go back up after anchoring Gyatso, despite running out of oxygen,” Wangyal says.

At South Col that night, Wangyal had to once again tend to an anguished Gyatso, who was screaming in pain due to his aggravated injury. After 36 hours, he could finally connect with Kohli and inform him about their success.

In his diary, Wangyal pens his thoughts on making the summit:

‘Lying in my sleeping bag I tried to think of the day which had passed. We had climbed Everest. What did I feel? Nothing at all. There was no elation, no sense of overpowering; I was exhausted and all I wanted to do was to sleep but that did not seem possible. Sonam Gyatso was in a bad way. He needed attention. Both my lilo and its pillow were punctured. Sleep, thus, in spite of oxygen, was neither deep nor restful. We had much to be thankful, for we were still alive and safe.’

By the end of the expedition, a record nine climbers had summited Everest, making it the most successful climb until then. On his return, Wangyal was awarded the Arjuna and Padma Shri awards. While he was part of other expeditions there on, he also served an assistant director in the ITBP and principal of the Sonam Gyatso Mountaineering Institute in Gangtok. He was awarded the Tenzing Norgay National Adventure Award in 2018.

These days, Wangyal is back in his hometown of Leh.

“When I look back, it’s really satisfying to have achieved so much from being a simple sepoy,” Wangyal says.