In 1965, a joint mission between India and the US looked to plant a spying device on the mountain in Garhwal. It led to a mystery that remains unsolved to this date.

First published: https://www.livemint.com/Sundayapp/g1GCx9n5O83AqHI4ClJAZP/1965-Nanda-Devi-spy-mission-the-movie.html

1965 Nanda Devi spy mission, the movie

A group of Indian and US mountaineers lost in the ice a nuclear device to spy on China from atop Nanda Devi. Now, a US filmmaker is attempting to unravel the mystery onscreen

It was the biggest moment in Indian mountaineering history. After two unsuccessful attempts previously, the first team of Indians had finally reached the top of Mt Everest in May 1965. Thus, India became only the fourth nation to have led a successful expedition to the highest peak in the world.

As the Air India flight carrying the successful team landed at Palam airport in Delhi, the tarmac was packed with people. A number of dignitaries awaited the mountaineers on their return from Kathmandu.

The leader of the expedition was Manmohan ‘Mohan’ Singh Kohli, who had also been a part of unsuccessful Indian expeditions in 1960 and 1962. A lot was at stake, then, when he was asked to lead the third attempt. Kohli lived up to all expectations—four parties comprising nine climbers reached the top.

After months of toil and dedication, it was now time for the team to bask in the glory. Even as Kohli descended the stairs and soaked in the adulation, he was asked to go to the tarmac at the back of the aircraft—someone was waiting for him. He thought it would be a surprise and so it was.

Kohli walked over and found Rameshwar Nath Kao, the first director of the Aviation Research Centre (ARC), awaiting him. What he thought would be a few words of praise and some thumps on the back turned out to be something quite different. There was no more time for celebration, Kao had a new mission for him.

Only this one was top secret and was to remain so for the next 13 years.

***

The story of the mission that followed, in 1965, make for the perfect plot for a potboiler. It has everything: China’s nuclear tests at the height of the Cold War, an insecure America, their ally in India, and a spying device that would be planted on a Himalayan peak, of all places, to monitor the activity of the Chinese… It had American Scott Rosenfelt, who has produced films such as Smoke Signals, Home Alone and Mystic Pizza, hooked.

“I was sent an article that appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in March 2007,” Rosenfelt says over email. “It was the story of the extraordinary incident, a failed CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) mission and a tragedy in the lives of all climbers who did this brave thing for their countries and got nothing in return. I was immediately taken with it and sought out rights to the project.”

The rights were first acquired from Kohli for his book Spies in the Himalayas in September 2007 and have been renewed three times due to insufficient funds. The film is being produced by Raashna Shah and Gopi Sait of Mulberry Films, and Rosenfelt’s partner Don Schneider on a tentative budget of US $20 million.

“We needed a great script to begin the process of securing cast and director. Once those things are achieved, the financing follows,” he says.

***

Though Kohli didn’t know it at the time, the Nanda Devi story had already started to unfold on the eve of the ’65 Everest expedition, when he had an unexpected visitor in his office. Barry Bishop was a top mountaineer-photographer and a part of the American team that had climbed Everest in 1963.

“I had no (prior) intimation of his visit,” says Kohli, sitting below a stunning photograph of Mt Nanda Devi in his office in Nagpur. He is now retired, living in Nagpur in the winters and Delhi in the summer—he owns hotels in both locations.

“He asked me if I would accompany him to Zemu Glacier in Sikkim. I thought he was quite mad, for he was well aware that I was leading the Everest team and how big a moment it was for the country. He simply said OK and walked out.

“I found it all suspicious, because he was a well-known mountaineer and he could have just approached the Indian Mountaineering Foundation if he wanted support for an expedition in India,” he adds.

Kohli decided to report the matter to Bhola Nath Mullik, who was a part of the Intelligence Bureau (IB), and requested him to keep an eye on Bishop—Kohli wondered why he was being asked to go to Zemu in Sikkim, which is close to the China border.

Little did Kohli know then that the American had been sent by Mullik himself to get a feeler of the task at hand.

As was the situation, the first nuclear test had been carried out in the Xinjiang region of China in 1964 (and while the Indians were on Everest in 1965, another explosion took place). While the whole world was keen to a keep a track of developments in China, India had her own reason. She had just fought a bitter war with China in 1962.

In the US, however, things were getting serious. Work was already afoot on a daring plan to spy on the Chinese.

“When they heard that I had put nine men on top of Everest, they knew that I was the right man to lead an expedition in India,” Kohli says.

***

The entire plan was hatched over a cocktail in 1964. Bishop was having a casual chat with Curtis LeMay, who was then the US Air Force Chief of Staff. The mountaineer happened to tell LeMay about the stunning views one could get of the Tibetan Plateau from the Himalayan peaks. The prospect of peeking into Chinese territory suddenly struck LeMay.

As the idea of planting a spying device on Indian territory got more real, Bishop started assembling a team of top American climbers. Once the Indians were back from Everest in June 1965, Kohli’s meeting with Kao resulted in him being appointed as the leader of the expedition to Mt Kanchenjunga (8,586 metres)—the third highest mountain peak in the world, where a spying device was to be planted.

Since it was high enough and located in Sikkim, which was an independent mountain kingdom then but under India’s control, it seemed ideal to the Americans. Soon, the Indians were whisked away to the US to meet their counterparts.

“Our passports were ready, as were the tickets. We were asked to spend the next few days wrapping up the receptions and festivities celebrating the Everest ascent. The team would have liked to spend more time, but as per tradition, we just took orders with an ‘aye, aye sir’,” Kohli, now 85, remembers.

“We had no free-thinking and few details,” adds Kohli. “I was told that we had to carry something to the summit of a mountain, alongside the Americans. What it was or the fact that it was composed of 80% of the radioactive material that destroyed Hiroshima were details we didn’t know. Nobody told us how dangerous it was.”

In Alaska, the team comprising the handpicked Indians and Americans was to climb Mt McKinley (6,190 metres) as team-building exercise. There, for the first time, they saw a replica of the device which was to be placed on the mountain. It was big. Kohli soon realized that it took about an hour for the constituent pieces to be assembled; carrying the extra weight in the thin atmosphere would pose further challenges.

“Even if you attempt to climb Kanchenjunga 10 times, you will summit only once. Then, to carry four extra loads of between 30-40kg to the top was stupid. To spend one hour to install it was the height of stupidity,” Kohli says, laughing.

So on his return to India, he gave his feedback to the Indian authorities at ARC. Kanchenjunga was declared unfeasible. A few other peaks were considered, in consultation with the Americans, and finally, the team agreed upon Nanda Devi.

“We took it as a mountaineering mission, as we were mountaineers first. And we were least concerned about the spy part of it,” Kohli says.

***

At 7,816 metres, Nanda Devi remains the highest peak which is completely inside what is considered Indian territory. It lies in the Garhwal Himalayas of Uttarakhand, providing tourists a glimpse of its glory from the ski slopes at Auli. Yet, it took years of persistence for an explorer or a group to get to the base of the mountain, given its location.

The mountain lies in what is today known as the Nanda Devi Sanctuary and sits pretty in the middle of double, concentric mountain ranges of equally formidable peaks. The only possible approach to its base is through the Rishi Ganga gorge, which can be accessed from the village of Lata.

Tackling the steep faces of this gorge is a task in itself, and it was only in 1934 that legendary explorers Eric Shipton and Bill Tilman managed to enter the sanctuary for the first time. Tilman came back two years later to make the first ascent of Nanda Devi alongside Noel Odell.

The mountain is revered as a Goddess by the locals, and there are a number of temples in the region dedicated to Nanda Devi. As a result, climbing the mountain was considered sacrilege and one of the most tragic stories is that of Nanda Devi Unsoeld.

She was named after the mountain by her father, Willi Unsoeld, an American climber and the first to ascent Everest via the difficult West Ridge alongside Tom Hornbein in 1963. The father-daughter duo made their way to climb the mountain in 1976.

But Nanda Devi suffered a stomach ailment on the mountain and bad weather made it impossible to evacuate her, resulting in her death at Camp 4.

The treacherous approach route, alongside the legend of Nanda Devi, made it a formidable start to the expedition. Then, to orchestrate the sheer volume of men and goods on the expedition was a logistical nightmare for Kohli.

To make matters worse, this was during the peak of the Indo-Pak war when each day would bring in reports of another attack and rumours of enemy paratroopers landing in the very region of their operation. This was to be one mission which would never be short of challenges.

***

Rosenfelt had his task cut out when he started researching for the film.

“At the time, outside of Captain Kohli’s book, there was not much to go on,” Rosenfelt says.

Kohli had co-authored the book, Spies in the Himalayas, along with Kenneth Conboy, a former political analyst, in 2003. Then, climber and author Pete Takeda heard about the expedition while climbing in Yosemite in the 1990s and decided to chase the story. He met Kohli, went climbing to Nanda Devi East (the twin peak of Nanda Devi) and wrote An Eye at the Top of the World in 2006. However, Rosenfelt steered clear of these books and conducted his own research—there exists a record of the incident in the CIA’s library of declassified documents.

“The film is not based on any book on the subject. I have interviewed members of the expedition besides Schaller (Robert Schaller was a part of the American team) and Kohli. They are excited about this and all have different points of view. Some are whimsical about it, others bitter. In fact, one of the Americans refused to talk based on the oath of silence they had taken when they signed up,” he says.

Most of the Indians and Americans who were a part of the expedition were legends in their own right. As of 2017, only a handful of these stalwarts survive, and they’re happy to let the entire saga be a part of their memories than bring them out to the public at large.

Gurcharan Singh Bhangu, who was a part of the Everest expedition as well as the Nanda Devi mission in 1965, put things in perspective. But he too chose to reveal little beyond the basic details.

“Look, I was a sportsperson and when it came to the interest of India and its people, that was most important for me. Of course, this was the time of the nuclear arms race, but for us, it was just another job. Our relationship with China was bad, US and Russia were clueless, and here was something that would help India. So we went right ahead to serve the nation. These are topics that should not be mentioned anymore,” he says.

The commercial motion picture, with a budget of $20 million excluding the actors’ fees, will feature an Indian and an American actor to play Kohli and Schaller, respectively, and is likely to be filmed in Seattle, Washington, Alaska, Washington D.C. in the US, New Zealand, and India. The script is currently being worked on. Ranbir Kapoor is being considered to play Kohli’s part.

“We are in talks with him (Ranbir) to play Kohli, but nothing is set until the script is finished,” Rosenfelt says.

He says, “We will do the second unit photography of the mountain from afar, but do most of the work in New Zealand.”

***

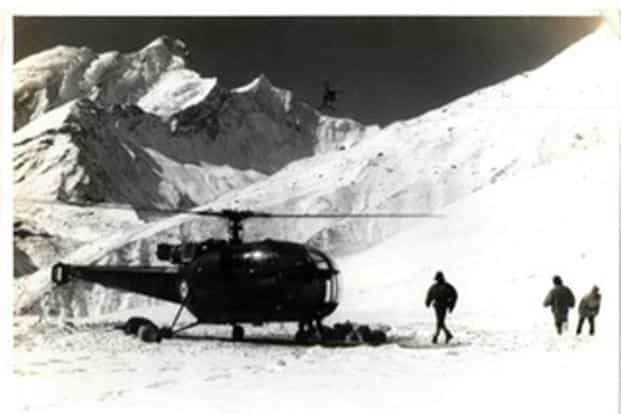

The Americans arrived in India in August 1965, with changed names, addresses and professions. The monsoon had subsided and the following month, the team started their approach towards the mountain. A World War II airfield at Gauchar in the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand was readied from where there were regular helicopter ferries into The Sanctuary. Once Base Camp was set up, the team started moving up the mountain in order to establish further camps.

One particular load that had to be ferried by the Sherpas was the generator to power the spying device. It consisted of radioactive plutonium fuel rods, which produced tremendous heat due to the radiation they emitted. It was the perfect aid to tackle the bitter cold on the mountain and consequently found a lot of favour among the Sherpas. They were happy to carry it for the warmth it provided, despite the weighing around 30kg, according to Bhangu.

Only their bosses knew how dangerous it could be and hence, the person carrying it was handed a white patch on his outer clothing that would change colour in case of any radiation leakage. Kohli also insisted that no person should carry it beyond four hours.

The plutonium was needed to power the spying device, once it was placed on top of the mountain. The Indians had nothing to do with it; it was designed by the CIA. When the Indians went to the US, a part of their exercise was to understand the assembly and they actually put together a dummy device to figure out how it was done.

Spies in the Himalayas describes the device like this: “There were four major components to the sensor, all connected by streams of wires and cables. Two of the pieces were little more than metal boxes placed atop posts to keep them off the snow and ice. These were the transceivers—labelled B1 and B2—that would relay the collated missile information to the base station elsewhere in India.

“The third component was the collection antenna that would snatch the telemetry data from the Chinese missiles. The six-foot-tall antenna looked like the standard television aerial found atop many American homes.”

“The final component, by contrast, looked far more exotic. Officially called a SNAP 19C (short for System for Nuclear Auxiliary Power), it was a thermoelectric generator capable of 40 watts of continuous output for two years. Deriving its power for the heat generated by radioactive decay, the SNAP was meant for use in devices placed at remote, unattended locations for extended periods.

“This was the first time it was being incorporated into a mountaintop sensor, but various classes of the system had already been successfully integrated into US government meteorological stations, as light on buoys, and in satellites.”

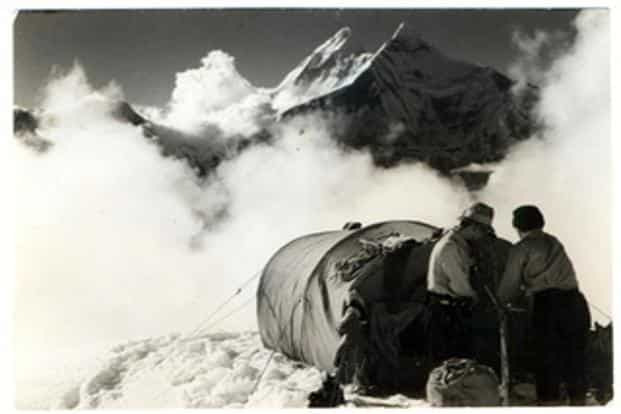

It all went as per plan, initially, and the men and the device were soon at Camp 4 (7,239 metres). Just when the summit was in sight, the weather turned bad and the climbers were stuck in a blizzard. It made little sense to risk getting caught high up on the mountain, given the fact that they were well past the end of the climbing season.

There were lives at stake and after much thought, Kohli, the team leader, called off the mission. Those at Camp 4 were asked to descend after stashing the device on the mountain, to be retrieved the following season.

The next year in May, a team comprising a few Indians from the previous trip and an American nuclear expert went back to the mountain. What they had realized from their first attempt was that not only was Nanda Devi a difficult mountain to climb, but they could also have done with planting the spying device on a lower mountain.

As a result, the team decided to bring back the device and plant it on the neighbouring Mt Nanda Kot (6,861 metres). It all seemed a simple exercise until they went back up Nanda Devi to Camp 4.

The device was nowhere to be found.

***

A number of search operations to locate the missing device have been futile since. Various equipment that could check for radioactivity were brought in, which too revealed little. Samples of water and rock were also checked for radioactivity but the tests came back negative.

The radioactive element in the missing device made it all the more important that it be found. If it were to contaminate the waters of the Rishi Ganga, it would do the same to the main Ganges river further downstream into which it drained. The Indian authorities were concerned about a natural catastrophe that would harm millions of people.

“For us, it was a failed mission. What made it worse was that no one had told us about the risk of contamination and that it could kill so many, in addition to damaging the environment. Had I known earlier, I would have made all attempts to bring it down, despite the bad weather,” Kohli says.

It wasn’t until 1978 that the mission first came out in public when Outside magazine published an article. By then, Kohli had joined Air India and was stationed in Australia.

“I was in my office when I opened the Sydney Morning Herald and there it was—a big news item with an even bigger headline. Two days later, I was asked by the chairman of Air India to rush to New Delhi and meet Prime Minister Morarji Desai.

“It had all become a headache and I had to sit down and give my account of what had happened. We had been specifically asked not to keep any notes or photos from the expedition, so all that I had was from memory,” he recalls.

A number of articles—waste from that expedition—continue to be found time and again, and there are abundant theories on where the device could be and the harm that it could cause.

Takeda feels that the device may still be in The Sanctuary and is probably under the ice in the glacier. “I do not feel the threat to the environment is significant because of the composition of the plutonium and its disposition. Plutonium would have to be vaporized or ground into very fine powder and then ingested in order to have a deleterious effect,” he says.

Kohli believes that modern technology that uses lasers and radar could help locate the device, but it would be an expensive affair that both Indian and American authorities should collaborate on.

The Nanda Devi Sanctuary has long been shut to civilians, though it is uncertain whether this was done after it was declared a UNESCO heritage site in 1988 or because of the missing device.

It remains to be seen how things change after Rosenfelt’s silver screen attempt on one of the most glorious mountains in the world—and the deep, dark mystery it perhaps still hides.