After an accident in 2018, Abhilash Tomy suffered life-threatening injuries during the Golden Globe Race. In 2022, he’ll be back at the start line to go the distance.

Abhilash Tomy.

First published: South China Morning Post

Comfort zone on the high seas

After a vicious 2018 storm that nearly killed him, celebrity Indian yachtsman and retired naval officer Abhilash Tomy returns for unfinished business in the Golden Globe Race

On September 20, 2018, Abhilash Tomy was sailing in the middle of the Indian Ocean. The closest continent to him at that point was Antarctica. He had been at sea for a little over two months and was running in third position as part of the Golden Globe Race.

The weekly call scheduled with race founder Don McIntyre brought unwelcome news. A storm was brewing above him, “vicious, but short and sweet”, with winds “well over 50 knots”. It was likely to hit him in a few hours, but since it seemed to be moving fast, McIntyre had his fingers crossed, hoping the sea did not get a chance to build up “really big”.

True to the forecast, the storm hit Tomy with fury. The winds changed rapidly, bringing towering waves from two different directions. Tomy said the sea was “very confused”, which eventually led to an accident.

His sailing boat, Thuriya, flipped over twice. When it popped back up on the second occasion, Tomy found himself stranded high up on the mast. He remembers falling anywhere between 5 to 9 metres and landing on the boom, a horizontal, aluminium pole that extends from the base of the mast.

As the storm continued to toss them around, he went about securing things inside the boat. But 10 minutes later when he tried to stand, his legs buckled under him. He realised something was gravely wrong.

There was no reason to take further risks – Tomy’s race was over. He sent out a text message and then lay in his bunk for more than three days, awaiting rescue. There were moments of despair as he thought of all that he had invested in the effort. But it was also the time he started dreaming of returning to the race one day.

“I thought of which boat to buy, maybe learn French to be able to communicate more effectively during the next race. Then I considered taking up Paralympic sailing, in case I was paralysed for the rest of my life. I was constantly chanting and breathing deep to stay calm. I knew I would get out of the situation,” Tomy recalled.

“It was just plain bad luck. And I think nobody could have survived that storm,” he said.

On September 4 this year, Tomy will be back at the start line of the same race in Les Sables d’Olonne in France. Over seven months or so, he will look to take on the 30,000-mile circumnavigation yet again to wrap up unfinished business.

“It’s a mental challenge, but then again, there are certain qualities which help you survive. I am happy being alone and don’t get bored with myself. And I’m very patient,” he said.

Tomy is no stranger to adventures on the high seas. While serving in the Indian navy in 2012-13, he pulled off a non-stop, solo circumnavigation in 151 days – at the time, only the 79th person in the world and the first Indian to do so.

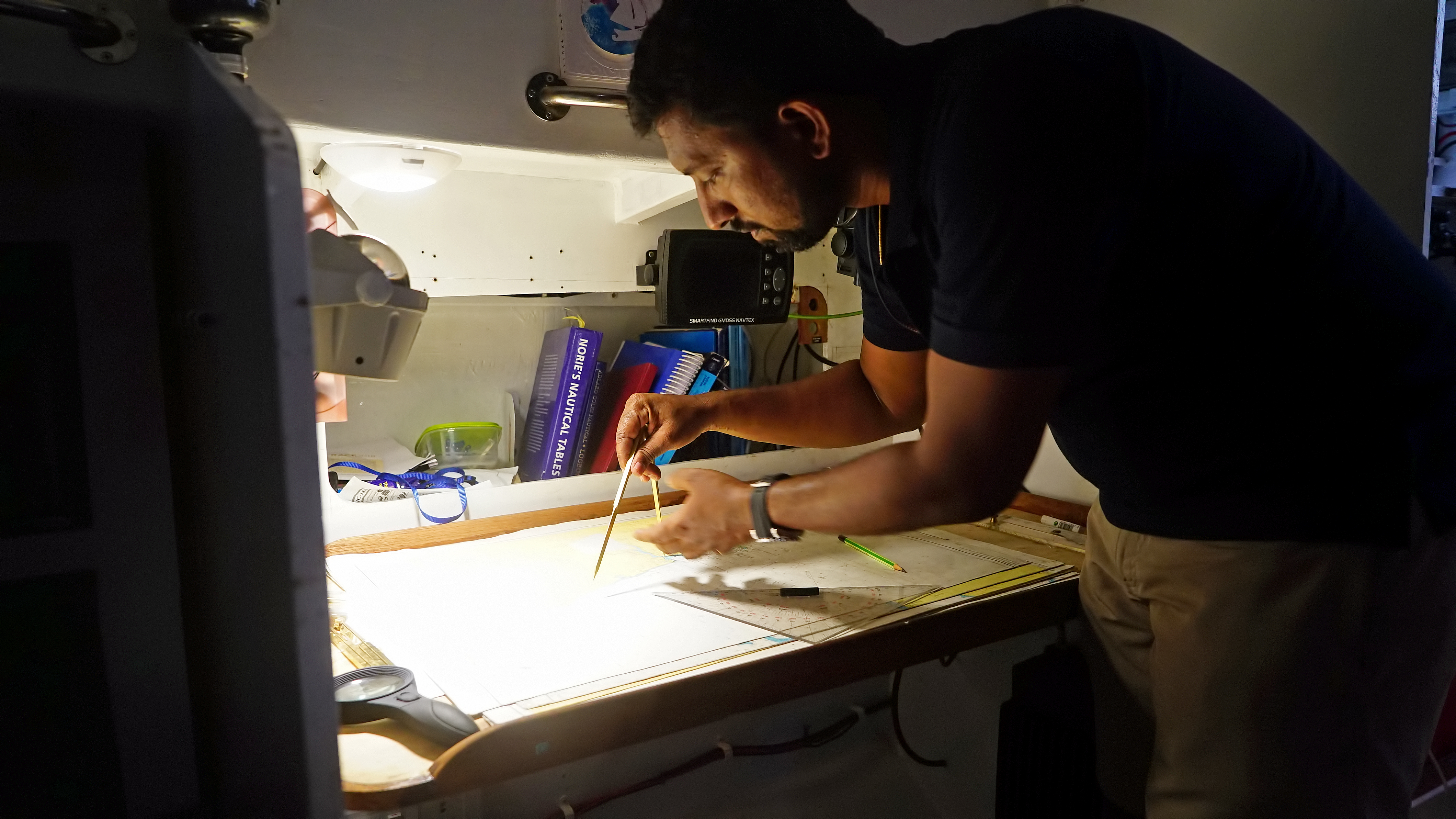

It earned him an invitation to the Golden Globe Race that was to test him further. Besides the challenge of sailing solo and non-stop, he would also be deploying traditional navigation techniques and equipment that were used during the first edition in 1968-69.

That race nearly killed him. The calm demeanour and his generous smile belies the turmoil that Tomy had to deal with after the accident. He had put everything on the line for that attempt.

The funding for the race had come from his own savings. Just a month before leaving for Europe, he had married his wife, Urmimala, who was also pregnant with their baby.

“We were paupers and under debt. But these are risks that he had to take because he genuinely loves what he does,” Urmimala said on the phone from their home in Goa.

“There is no money, no personal glory – only passion. You cannot tie down men like him and being with him meant that I had to let him go.”

The next time she saw him, Tomy was bound to a hospital bed in New Delhi. Five bones of his vertebrae had been fused into a single piece; his legs had no muscle, only bones and fat. Just sitting up caused him excruciating pain. But Tomy was stubborn. He would not let anyone help him. All along, the fight was in his head.

During those early days, Urmimala recalled Tomy not being in a very good state of mind. He would not talk much about the accident either. Soon, she started engaging him in conversations to help him deal with the incident.

“The past was constantly tugging at him. The storm kept playing in his head and for very long, he would dream about it as well. It affected him to quite an extent and required a lot of counsel- ling between us,” Urmimala said.

“When your mind is not in the right place, the body cannot recover. You have to be able to face the past to be able to live in the present,” she said.

Two weeks after the surgery, he returned home in a wheelchair. At the time, Urmimala was heavily pregnant with her baby. She remembers Tomy despondent, every time he realised that he could not care for her.

A tedious recovery followed. The rehabilitation involved physiotherapy sessions, work in the swimming pool, hours in the gym, Pilates and kick-boxing.

“At one point, I could do squats with just one leg. But I was so badly off that I could bend just an inch and that too with my back against the wall. That’s when it all sank in,” Tomy said.

But just a couple of months after the accident, Tomy returned to Delhi, this time on his feet. And four months later, he had cleared his medicals to resume flying duties in the navy.

“The medical tests for flying are the most difficult. Once you clear that, there are emergency drills where you are made to enter the cockpit blindfolded, then the entire aircraft is submerged in water and you must escape from it. I did everything possible to prove my fitness and fly again,” he said.

Even as he grew stronger, Tomy threw himself into looking after the family and spending time with his newborn, Abhraneil. At the back of his head though, he was dreaming of the race.

He returned to his books on celestial navigation, a subject he admits he had flunked while in the navy, and started analysing data that he would need for the next attempt.

He took on courses related to medical care and survival. Last year, he quit the navy to focus all his attention on the race. He said he owes it to his family for their support, despite all the hardships.

“My mother called me when I couldn’t walk without crutches and said, ‘I hope you are going to stop all this nonsense now’. And I said, ‘If I’m better I may go back to sailing’. And she said, ‘Good, that’s exactly what I wanted to hear from you’.”

Urmimala said: “I think the birth of his son cured him completely. And though none of us wanted to hear about it for a long time, the preparation for the next race kept him going. We always knew that he was going to go off again on some adventure. Time with him is always limited.”

Through a friend, Tomy was able to connect with Bayanat earlier this year. The United Arab Emirates-based, company, which provides comprehen- sive world-class geospatial artificial intelligence solutions to various sectors, decided to sponsor his race last month.

“A year after a life-threatening injury, he was back to sailing. The determination and courage that was shown by Abhilash during the 2018 race is something that resonated with us,” Hasan Al Hosani, the chief executive officer at Bayanat, said.

“During his journey, Abhilash will aid in ongoing scientific work, including the collection of water samples, which can be analysed for up-to-date insight on the presence of microplastics in the world’s oceans.

“In addition, a small section of the sailboat will be painted with special paint, which will serve as a reflectance target for satellites, presenting a one-of-a-kind opportunity for Bayanat to collect calibrated data during the race,” he added.

These days, Tomy is in the Netherlands, readying the boat alongside designer, Dick Koopmans. The 32-foot, UAE-registered vessel is being given a refit to customise it to his needs.

“It’s lighter and faster than the last one. The most important piece in this race is the boat. Even for a gifted sailor, there’s no point in racing if the boat is weak. It’s a long list of things to be done and we’ll take about two months to get the boat ready,” Tomy said.

Come September, he will be back in an environment where he has found his comfort zone through the many highs and lows.

“When I think back about that race, there is no remorse or regret. I treat them all as experiences, but I don’t qualify them as good or bad. I think it comes from spending a lot of time alone at sea,” he said.