There was a time when a women’s expedition was incomplete without Chandra Prabha Aitwal. As she cools her heels in Uttarkashi these days, she reflects on her epic first ascent of Nanda Devi in Garhwal.

First published:

https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/9Zs1NnTHmRJoxEFcYEAJkN/Chandra-Prabha-Aitwal-The-first-lady-of-Nanda-Devi.html

Chandra Prabha Aitwal: The first lady of Nanda Devi

As the climbing season brings in stories of triumph and tragedy, we meet one of the first women to summit Nanda Devi

Getting to the top of a mountain usually calls for a celebration. More so if it’s a first in mountaineering history. When Chandra Prabha Aitwal got to the top of Nanda Devi (7,816m) in 1981, behind Rekha Sharma and Harshwanti Bisht, it was the first time women had set foot on the second-highest peak in India.

But neither does she have any photos of the feat, nor any memory of the fascinating view from the top. For Aitwal summited the peak in relative darkness, against all odds and with just about enough strength to say a little prayer and make her way down the moonlit slope.

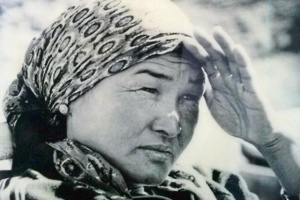

Aitwal’s story is one of grit and perseverance at every opportunity that came her way, which explains why, at 74, she still dreams of “one last stint in the mountains” even as another summer of climbing heads towards the finish.

It’s a cloudy Sunday morning in Uttarkashi. A diminutive lady in salwar- kameez answers the door, and when I tell her I’m looking for Chandra didi, as she is known in mountaineering circles, a familiar smile breaks out on her face. “Main hi hoon, andar aa jao(that’s me, come in),” she says.

At first sight, it’s hard to believe this petite lady had attempted Everest (8,850m) thrice, and successfully scaled peaks such as Nanda Devi, Kamet (7,756m), Nanda Kot (6,861m) and Black Peak (6,387m), to name a few. Then again, it’s even harder to believe what she’s achieved, considering mountaineering happened quite by chance in her case.

Aitwal was born in Dharchula in Uttarakhand’s Pithoragarh district, though her family belonged to Chhangru, which lies across the Mahakali river in the hills of Nepal. The end of winter would see an annual migration to Nepal, where she grew up running up and down terraced fields, tending cows, helping with farming and collecting wood. She was happier dealing with household chores than the travails of daily school, and regularly joined her father when he visited Tibet to trade.

“I had to be thrown out of the house and walked to school, else there was a chance I wouldn’t turn up. I was around 17 or 18 years when I was in class VI, so you can figure it out for yourself,” she laughs.

If it wasn’t for her elder sister, who took on the role of guardian after their parents died when the children were young, Aitwal would never have pursued an education. But she crawled through her studies and led an ordinary life as a teacher in the Government Girls Inter College in Pithoragarh.

All that changed when the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering (NIM) in Uttarkashi sent out a circular, inviting government teachers to be part of the basic mountaineering course. By the time she got her opportunity, she was 30.

After proving her ability on peaks such as Kedar Dome (6,940m) and Bandarpoonch (6,316m), Aitwal was noticed by the Indian Mountaineering Foundation, and in 1981, was picked as part of an expedition that looked to put the first women atop Nanda Devi.

“When we were training for Kamet in 1976, a men’s team was to go to Nanda Devi. These were established mountaineers, yet they were in awe of this peak. I realized then that there was something about this mountain, and was overjoyed when I was picked for the expedition a few years later,” she says.

While Everest and K2 may make for popular mountaineering blockbusters, the legend of Nanda Devi is a saga that has enchanted followers for years. For one, the mountain is considered to be a peace-giving goddess who is worshipped by villagers in the region. Yet, over the years, a number of failed attempts and casualties have been attributed to the wrath of the goddess.

Nanda Devi’s location has made it an especially difficult challenge. The twin peaks are guarded by double, concentric rings of snow-capped mountains that comprise the inner and outer sanctuary, respectively, and make the walk to Base Camp nothing short of a slog. If the high passes are to be avoided, as is scaling the steep walls of the surrounding mountains, the only feasible approach is via the Rishi Ganga gorge that penetrates both layers. Despite being the preferred approach, however, this traverse too is a daunting task, considering the near-vertical walls of the gorge that climb from the Rishi Ganga river below.

As a result, attempts to approach the mountain while trying to locate new trade routes to Tibet in the 19th century proved futile, until Englishmen Eric Shipton and Bill Tilman made a bold attempt with a lightweight expedition, and managed to trek up the gorge in 1934. A couple of years later, Tilman and Noel Odell were the first men to stand atop Nanda Devi. It was only in 1964 that another party, led by Indian veteran Narendra “Bull” Kumar, managed to put the second set of men on the peak.

Until these expeditions made their way into the sanctuary, it was a relatively untouched area of the Indian Himalayas. As Kumar observed after his climb: “It is hard to conceive of a bowl, full of luxuriant grass and flowers of delicate hue; of partridges calling to each other across the gay scene; of bharals contentedly ruminating from their high, rocky, silent perches; of all this warm and secluded life enclosed by an icy, impassable and treacherous ring of high mountains, where blizzards blow constantly and living things do not dare to venture. But such is the reality of the Nanda Devi Sanctuary.”

For all its splendour, success on the mountain was met with tragedy, the most heart-wrenching being the death of Nanda Devi Unsoeld. Named after the mountain by her father and renowned mountaineer Willi Unsoeld, she and Unsoeld attempted the peak in 1976, but a bout of illness and bad weather meant that Nanda Devi died on the mountain as her father waited helplessly at a lower camp.

A failed attempt at planting a nuclear-powered spying device on Nanda Devi in 1965 had disastrous consequences; a radioactive substance lost on the slopes remains missing to this day. It is considered to be a major reason why the sanctuary is off limits for trekkers today.

A lot was at stake, then, in the August of 1981, when the 11-member team led by a colonel, Balwant Sandhu, set off from the village of Lata in the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand. The approach to the mountain was via the Rishi Ganga gorge but for the team, traversing the granite slabs before Patalkhan proved to be a task.

“There were stone slabs as smooth as slate, and it was impossible to traverse this section without ropes. A foreigner had slipped and died there a few weeks earlier. It was the first test of our endurance,” Aitwal says.

A week’s trudge got them to Base Camp and after a few days’ rest, the team started ferrying loads up the mountain to set up camps. The deputy leader of the team, Aitwal felt strong as she made consistent progress, but for a niggle that would prove to be a nightmare in the days to follow.

“I was fine until I opened the route to Camp 3, but on my return to Camp 2, I developed pus in one of my ears. One thing led to the other, and soon I had a running stomach because of which I had to return to Base Camp,” she says.

As the team recuperated at Base Camp, Aitwal was a wreck, losing strength each day due to a severe case of amoebiasis. She was left behind as the rest of the team proceeded up the mountain for the final summit push. Her saviour came in the form of P.D. Punekar, a doctor with the army expedition that had camped close by and was to attempt the climb after Aitwal and Co.

“I was lying in one corner of the tent when he (Punekar) came to see me. He was my bhagwan (god), because the expedition was pretty much over for me at this point. I have never seen anyone inspect what I kept throwing up with such interest. He prepared a magic potion for me, which I was to sip while climbing, and asked me to refrain from eating. The following day, I set off up the mountain alone,” she says.

After two days of climbing, Aitwal caught up with the rest of the team at Camp 3, but along the way she realized a lot of her stashed equipment had been taken by the others, who thought she would not be coming back. She had to wait to borrow essentials from those descending, and even shared a sleeping bag with Harshwanti Bisht at Camp 4.

On 19 September, the team was to attempt the summit. Aitwal roped up with Sonam Paljor for the final push behind the other two pairs, but slow progress meant that it was dark by the time she got to the top.

“I summited in darkness, but the moon was rising and, gradually, I could see the shimmering snow on the nearby slopes. Summiting has a different thrill associated with it, whether it’s in daylight or in the dark. You feel as if you’ve seen heaven; it cannot be put into words,” she says.