Alex Honnold talks about his epic climb up El Capitan, which has been captured in the Oscar-winning documentary, Free Solo

First published:

https://www.firstpost.com/living/free-solo-how-rock-climber-alex-honnold-scaled-the-3000-feet-high-vertical-face-of-yosemites-el-capitan-6632001.html

Free Solo: How rock climber Alex Honnold scaled the 3,000-feet-high vertical face of Yosemite’s El Capitan

His journey to the El-Capitan summit in 2017 was documented by director Jimmy Chin in the Oscar-winning film, Free Solo

He rolled out of bed with a mild throbbing at his temples. Binge watching films the previous night had clearly taken its toll. 33-year-old Alex Honnold woke up to prepare for his shoot at an ungodly, predawn hour, which was only secondary to what he was actually setting out to do that day.

After an early breakfast of milk and muesli spiced up with a dash of condiments, he drove off to face the camera, and a 3,000-feet-tall granite wall — the El Capitan, a giant monolith in California’s Yosemite National Park. Much like Honnold, a large number of climbers have gravitated towards its summit over the years; only this time, he was slated to take the lead.

The film crew led by director Jimmy Chin, who’s a rock climber himself, was in position and on edge, as Honnold readied for the final shot of Free Solo, which went on to bag the Academy award for ‘Best Documentary Feature’ this year. They knew there wouldn’t be a second take this time around. They also realised the frightening possibility of filming Honnold fall to his death. For the American free solo climber, that morning held hope for the fulfilment of his decade-old dream. And this time around, there would be no ropes to protect him.

What is free solo climbing?

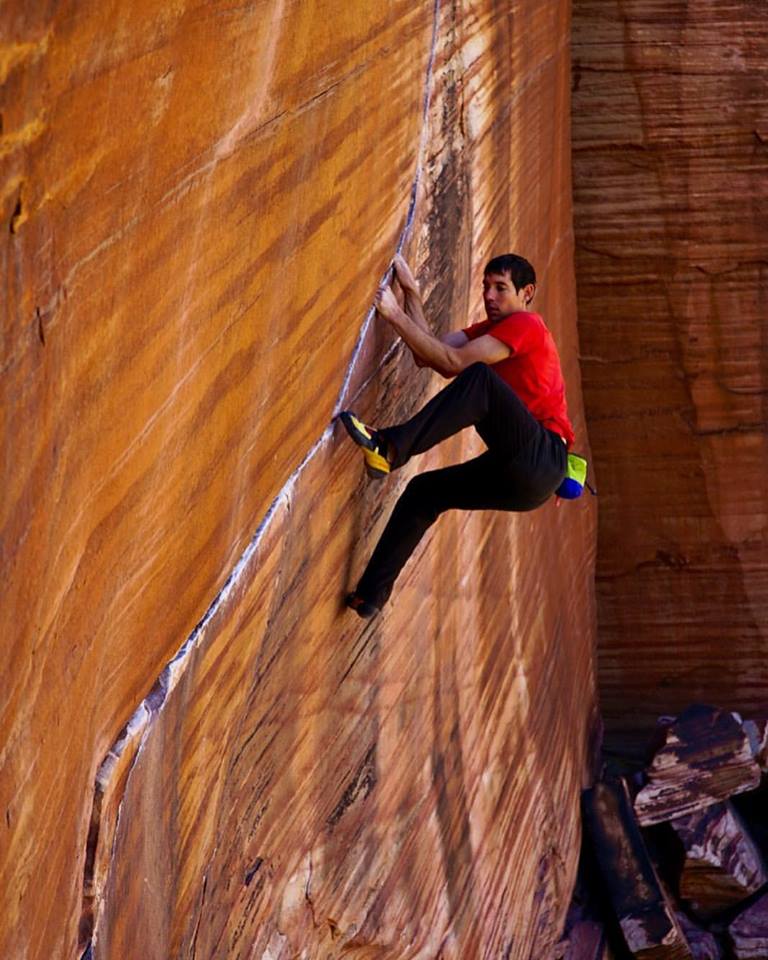

Free soloing, or what Honnold has been practising for over two decades, is a form of rock climbing performed without the help of ropes, harnesses, or any other equipment. In other words, it’s a trade-off between art and just outright audacity — perhaps even stupidity — given that there is no protection in case of a fall. The possibility of ending up with broken bones makes way for a certain death the higher one goes. It’s how climbing has been perceived in its purest form by a few like Honnold.

“I consider free soloing to be a cross between a sport and an adventure. I love the uncertainty and going in the unknown, the exploration,” Honnold says.

‘Psyched’ is a popular term in the climbing dictionary, especially Honnold’s. It’s what he considers as bare necessity for taking on a climb.

“It’s mostly a state of mind, just excitement about what I’m doing. But it also manifests as a physical feeling, you know, jitteriness or nerves or energy, feeling restless to some extent. I think a lot of those you feel physically, even though it’s really just manifestations of excitement,” he says.

That excitement, in turn, needs to be reigned in with a monk-like consciousness when suspended hundreds of feet above ground, supported purely by one’s bodily strength. There’s no room for any distraction, manmade or natural, until the climber is one with the wall she or he is climbing.

“I’m sort of used to the various features on the wall — bees, moss and sand, since it’s all around when I’m doing the preparations. It’s the same as going for a walk in the woods, how you’re just used to all the birds around you,” he explains.

Honnold makes it sound so casual that it’s easy to forget the fatal risk associated with the act. His attitude has even earned him the moniker, Alex “No Big Deal” Honnold, in climbing circles. However, what has been termed as arguably the greatest climb of our generation was executed with the looming danger of life loss, armed with the ability to enjoy oneself most of the times, with an unfettered vision to redefine what’s possible.

Where it all started for Alex Honnold

Honnold’s father, Charles, had infected his son with the rock climbing fever, and like most others, it started off in the confines of a gym. Charles had even secured second spot at the National Climbing Championship in 2004. However, with his father’s death, climbing took a different turn for Honnold.

The year following his father’s demise, Honnold borrowed his mother’s minivan, and used the money from his father’s life insurance to fund his travel through wildernesses and dizzying heights.

Embracing a nomadic life, the free soloist drove across the US in search of tougher terrains to take on and steeper mountains to scale. More often than not, only his minivan stood witness to him achieving impossible milestones that ultimately led him to El Capitan. Had it not been for his extreme introversion, Honnold may have taken to a different sort of climbing that involves journeying with a partner or in groups. But most of the times, the climber would feel too shy to go seek out a partner. He was at ease with being a complete misfit in the community right from the beginning.

“Soloing goes with being a total loser,” Honnold has admitted in the past.

As a result, each time he successfully finished a climb, it took a while for the rest of the community to take notice of what he had achieved. For instance, one of his early climbs up the 1, 200-feet-high Moonlight Buttress in Utah’s Zion National Park was mistaken for an April Fool’s joke, as he had ascended it on 1 April, 2008. Five months later, he had scaled the Northwest Face of Half Dome, another 2,000-feet-tall wall in Yosemite. He expected and needed no acknowledgement from anyone about his feat, being content with what he had accomplished. But as soon as the word spread, the rock climbing world sat up and took notice of this strange young adult, who was rewriting the rules of the game.

It was only in 2009 that Honnold allowed himself to be filmed, and publicly announced his arrival in the rock climbing arena. Back then, not many knew that he had already set his eyes on the El Capitan summit.

“The reality back then was that when I looked at the wall (El Cap), I was full of fear. It was horrifying to think about. For many of these years, I would drive to Yosemite, look up and then think it’s totally impossible. So I would go back and sit on it for another year,” he recalls. “I think what slowly changed happened with a lot of practice and preparation. And just broadening my experience,” he adds.

The first proper film that he shot for was Alone on the Wall (2010), for which he went back to Half Dome to recreate certain sections of the climb.

“It wasn’t documenting in a real sense, so it made for a nice little film but not a documentary. Free Solo is completely different because it’s all totally true. They were living with me, documenting everything for two years,” he says.

Soon, Honnold was signed up to be a part of a team of athletes for The North Face, an outdoor sports gear company. This deal took him to mountains outside the US as well.

Back home, he continued to pursue his El Capitan dreams by setting off on free solos up big walls and occasional free climbs (similar to a free solo, but with a rope for protection) of El Cap, Half Dome, and Mt Watkins. All of these added up to roughly 7,000 feet at one go, and in 21 hours, alongside another promising climber, Tommy Caldwell. With every new challenge, Honnold discovered a little more about his style of climbing.

“When I was young, I was maybe a little bit hungrier and I just kind of charged into the climb a little more. I think now I’m a bit more careful,” the athlete says. “Even after climbing for a while, it’s not as if I’m remembering specific movements. You just remember it like a long-flowing sequence, just like a dancer. I could tell you every move on the route at the end of the day, not because my memory is particularly good, but just because that’s what I do.”

Up the El-Capitan

Over time, Honnold had zeroed in on the Freerider route up the southwest face of El Capitan for his free solo, slated to be his most definitive climb till date. There on, he would identify and remember rock features on subsequent climbs while taking the route, rehearsing and choreographing accurate moves for over a year.

“After two years, I finished all the sections on the wall that I had to work out and basically had a moment. I realised I should do it now, because I was never going to be better prepared for it. It was either I do it then or never do it. And by then, I had invested so much that I wanted to do it,” he says.

A climbing accident and the consequent ankle injury briefly disrupted the schedule. But in the fall of 2016, Honnold set off to take on his decade-long dream.

It was still dark at the time Honnold started off. However, by the time the first rays of the sun had hit the wall, he’d abandoned the climb at a feature called the Freeblast slabs.

“I was pretty nervous because I was well prepared for the second half of the route. So I knew that the Freeblast slabs were going to be hard. Sure enough, when I got there, I didn’t know exactly what to do. The conditions weren’t ideal, so I basically got really scared and just gave up,” he recollects.

“It’s the first time I’ve ever turned around on a major free solo. I’ve done it in the past, just because I wasn’t motivated or feeling it. But I’ve never actually given up on something hard and challenging that I’ve really been prepared for. So to me, it felt like a big failure,” the soloist admits.

The final climb

Finally, in June 2017, Honnold was back. The injured ankle had gone through several rounds of rehabilitation and the shoe fit better.

“Basically the foothold felt a lot more comfortable and I had spent a lot more time practising the lower slabs,” he says.

The crew too decided to shoot the most crucial parts of the climb using remote cameras, so as not to distract Honnold during his climb.

He successfully crossed the dreaded Freeblast slab this time, and went on to focus on the climb ahead. The few times he paused was to rehydrate, tighten or loosen his shoes, and to answer nature’s call.

The film’s visuals appropriately justify the extraordinary nature of Honnold’s feat, with gripping shots capturing the expanse below him unfold gradually, and nerve-wrackingly. After 3 hours and 56 long minutes, Honnold topped out and accomplished the first free solo of El Capitan.

“I am quite proud of the climb and my favourite part is definitely the climb at the end. It’s great to see such good execution of something that I worked so hard for,” he says.

“But I think while watching it for the first time, it was quite challenging to see all the feelings between me and my girlfriend or my family. Basically, the social scenes were really difficult to film. There are a lot of things that are hard to watch for me, but you know, they’re all true, so I guess I have to live with it,” Honnold signs off, as he also prepares to live with the expectations that come with being the most radical climber of our times.