Life seemed uncertain for Pavitra until she started life afresh in Belgium. Today, she’s a champion sport climber, with eyes on the Paralympics in the time ahead.

First published: https://www.climbing.com/people/profile-of-paraclimber-pavitra-vandenhoven/?fbclid=IwAR1FIOM3AMvVwOxzsIl9m_Tm7OlZ5YmbAXnDb5mTHAvGx5Eb5utVdYejMLM

From India, Through Belgium, to World Cup Gold: One Climber’s Journey to the Top of Paraclimbing

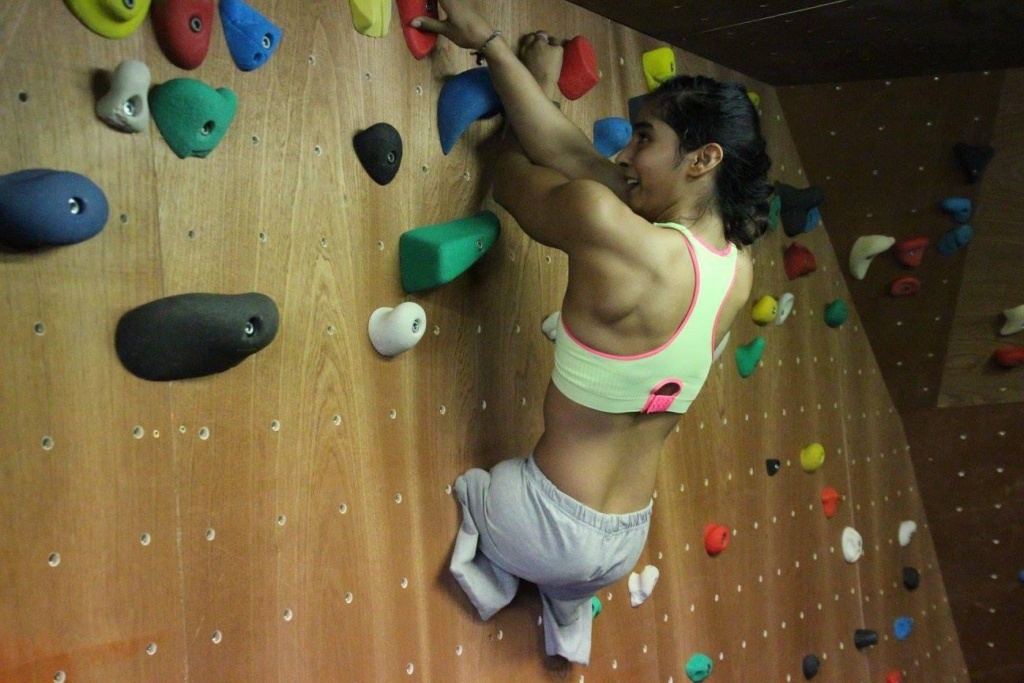

Pavitra Vandenhoven was adopted by a Belgian family at the age of five. It set off her climbing dream that has today led to two World Cup golds.

Pavitra Vandenhoven couldn’t sleep. It was the first night at her new home in Sint-Niklaas, Belgium, and the surroundings looked rather strange. Until then, the five-year-old had slept in a large shared room alongside other orphans like her in India. Craving the connection of her absent friends, Pavitra grabbed the crib’s railing with her little hands, hoisted herself over the top, and crawled to her parents’ room.

That first night was a wake up call for her mother, Christel Van de Voorde. Pavitra was born without legs and often relied on her mother to move from room to room. Van de Voorde was impressed—even if she couldn’t yet grasp how her daughter had managed to escape the crib. Van de Voorde, a climber herself, began to wonder, Could Pavitra become my climbing partner?

*

The IFSC Paraclimbing World Cup in Innsbruck in June 2021 was the culmination of a 17-year journey that began that Sunday morning in Sint-Niklaas. Pavitra felt nervous. Adrenaline pumped through her body despite her best efforts to maintain composure and the long wait in isolation seemed endless—her reward for qualifying in first for finals. But when the announcer finally did call her out, Pavitra had taken charge of her nerves and climbed with confidence, earning her first World Cup gold, a feat she repeated a few weeks later in Briançon. She finished the year with a first place finish at Moscow’s World Championships, announcing her arrival to the paraclimbing stage.

Climbing as a disabled person—alongside her congenital amputation, Pavitra, 22, also has four fingers on the left hand, two of which are fused—is just one of several challenges she has faced in her life. First among these was her upbringing. Pavitra lived in a Kolkata orphanage until 2003—a wholesome, family experience for her looking back—but one that left her wholly unbalanced as she struggled to integrate into her adoptive family. She struggled with the concept of a mother and father and couldn’t communicate with them in their native Dutch tongue.

“We had seen a few photos of Pavitra through an organization in Belgium that works with kids with disabilities. I went to pick her up in Kolkata with my son, Nokah. I was really nervous and so was she, running away and peeping from behind a chair.” Christel recalls. “Then she came looking for me, and in that moment I knew it would be alright.”

Christel had been in this situation before. She and her husband, Paul, met in 1981, and by 1990 they had adopted the first of their four children, Nokah, and three years later, their first daughter, Manja—both born in India. Christel was a recreational climber and loved sharing the local crags with her children. But it was with Pavitra that she developed a special connection to climbing.

“I was always curious as a child, climbing on and off absolutely anything. The first few times I just watched Mom climb, until she decided I should give it a go,” Pavitra says. “At seven, I started climbing at a small gym near my home. It was the perfect release for my energy.”

“My mother was very worried initially, since I used a regular harness which didn’t secure me completely,” she adds. “I had to stop climbing briefly until they had a special one made for me in Germany.”

Once the custom-made harness was delivered, her parents’s initial anxiety transformed into sheer joy while watching their daughter climb. She thrived on the gym’s energy, mingling with people who shared the same enthusiasm for climbing and relished not being bound to a wheelchair. Pavitra initially relied on her impressive upper body strength to gain upward progress, but she soon discovered a swinging technique to latch the most distant of holds. Back at home, Christel, a trained route-setter, built a bouldering wall in the attic with routes that were both accessible and challenging for Pavitra; the sport was quickly becoming central to her identity.

*

The real challenges for Pavitra came outside of climbing. Her neighborhood’s school had yet to teach a disabled person, and its administrative staff worried that the building would not be accessible for her. Rather than update the structure, they refused to allow Pavitra a place to learn—until Christel fought for her inclusion. “Most disabled people are kept indoors in Belgium. So at school, they weren’t exactly sure what Pavitra was capable of when it came to learning.” she says. “Then there was the question of her mobility, since she was in a wheelchair. I wanted her to go out and do all the things that I could do.”

Pavitra’s early days at school were a breeze. Classmates loved her unique skills, whether it was a confident handstand or walking using her hands. But Pavitra experienced discrimination as she entered her teens. She was always the last chosen in group activities and often excluded from birthday parties. A few classmates used her disability to their advantage, inviting her to amusement parks so they could skip the long queues.

“Even today when I tell people I’m pursuing applied psychology, they are like, ‘Wow, you also study.’ Perhaps they think I’m disabled in the head as well,” Pavitra says. “People hurt me a lot and it was hard for me to accept my disability initially. Fortunately I had some good friends who stood up for me.”

Pavitra says her social life improved in 2006 when the family adopted their fourth child, a girl named Stefia, who is also disabled and from India. The girls had a common understanding that Pavitra had not yet experienced and they quickly bonded. Pavitra was a role model of sorts, and the duo spent almost all of their free time together swimming, as Stefia was (and still is) a talented competitive swimmer. But despite her new sister and time in the water, Pavitra relied heavily on climbing as a distraction from the hardest parts of her life—often to a fault.

“It started out as something fun. [But] when I started competing, it got monotonous: just going out and training every single day. I didn’t realize the gradual impact it was having on my life,” she says.

Pavitra went to her first local competition at age 10. As the only disabled climber, she was cheered on by the crowd who had never seen anything like it before. The father of one of Belgium’s top climbers, Anak Verhoeven, asked if she wanted to compete regularly. A quick chat with her mother followed, and the trio decided to work towards Pavitra’s goal of becoming a professional climber someday. “In the beginning, I was quite insecure because I mainly climbed to inspire people and not to win. Then I got curious and decided to try new things,” Pavitra says.

The weekly climbing sessions increased in frequency and replaced her casual days at the pool with Stefia. To further strengthen her arms, Pavitra began walking on her hands more frequently and avoided the wheelchair whenever possible. Verhoeven’s father taught her how to handle the mental pressures of competing as well. She was soon winning competitions around Belgium, then travelling across Europe to compete.

“Since there were few climbers with her disability, I asked her to compete with better climbers in the higher category,” Christel says. “But I always told her that she didn’t have to climb for me. She had to do it for herself. And have fun along the way.”

Since 2013, Pavitra has been a regular feature at domestic competitions, winning the Belgian Youth Cup and the Belgisch Championship. She also made the cut on the Belgian climbing team, representing her country at the Paraclimbing Cup in Edinburgh and the World Cup in Sheffield, both in 2017. The latest World Cup triumph is a sign of things to come as she trains for the Paralympics in 2024 where Sport Climbing will debut.

“It’s a dream to be at the Paralympic Games. Unfortunately there is little financial support from the federation. My parents fund everything at the moment. It’s a lot of money and a sponsor will really help me move up the ranks,” Pavitra says.

Besides chasing competitive climbing in the future, Pavitra also dreams of returning to India someday to explore her country and brush up on the smattering of Hindi that she’s kept in touch with since. “My roots mean everything to me. I’m proud of the colour of my skin,” she says. It’s one of the things that greatly humors her even today: that most people fail to think about the color of her skin because she’s disabled. She says there are many facets of her life that overwhelm her, but she finds solace in sharing her experiences. And that through climbing, she wants to inspire others in the disabled community to take up the sport.

“I am adopted, have a different skin color, and am disabled. I’ve had my own struggles over the years, but climbing has taught me to become more self-confident [and] stronger both physically and mentally,” Pavitra says. “It has helped me make peace with who I am. And I would like others to feel the same.”