It’s hard to miss the “di ding ding ding” of a Jawa motorcycle, especially if you were around in the 60s and 70s. This book is a comprehensive documentation of the journey of the humble motorcycle.

First published: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/know/the-return-of-jawa/article26886503.ece

The return of Jawa, the forever bike

As the rugged machine is reincarnated in a modern avatar, a look back at the iconic motorcycle’s decades-old love affair with India

He didn’t have a driving licence — but those were the days when you didn’t really need one. What you needed, apart from the wind in your hair, was a Jawa bike — and his uncle had one. As a young student in Pune, Adil Jal Darukhanawala would often zip off on the motorcycle.

Bikes, clearly, played a big role in his family. One of his first pictures in the family album has him seated on his father’s motorcycle. The year was 1957 and he was six months old. But bikes were an intrinsic part of a great many other lives, too. And as the iconic Jawa — later known as Yezdi –— returns to India after more than two decades, sepia-tinted pictures and memories are popping out of crevices about the bike that once symbolised a certain kind of lifestyle.

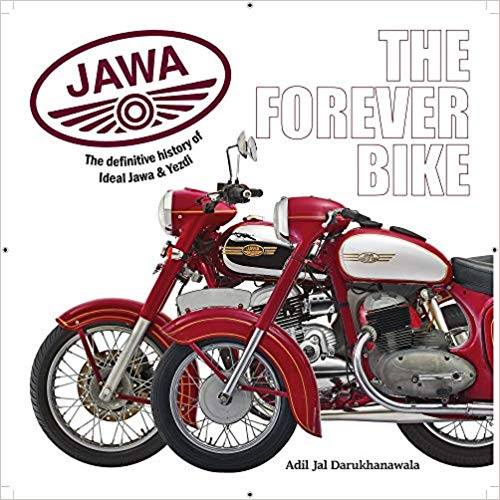

Darukhanawala was witness to the motorcycle’s own journey in India, as it endeared itself to ardent bikers everywhere. It’s a legacy he passionately relives in the book Jawa — The Forever Bike; The definitive history of Ideal Jawa & Yezdi.

Alongside recapturing the bike’s glory days, the well-researched book offers a lowdown on the birth of the motorcycle industry in independent India.

Early days

Before Independence, a clutch of foreign motorcycles such as Royal Enfield, Norton, Triumph, Indian, BMW and BSA had made their presence felt on Indian roads, with a majority of them being British. Only a handful of Indians could afford to import them. In the late 1930s, the first Czechoslovakian bike, the two-stroke CZ, arrived in India.

Jawa lovers have to thank four men — brothers Rustom and Boman, and their nephews Farrokh and Noshir Irani — for getting the Czech-made bike into India. In the 1930s, Rustom and Boman had set up Ideal Motors in Bombay to import Sunbeam and BMW motorcycles. During World War II, realising the need for cheap mobility, Rustom and Farrokh, who was running FK Irani Wines in Pune, decided to import Jawa motorcycles from erstwhile Czechoslovakia.

Later, they were joined by Boman and Farrokh’s brother Noshir, who had entered the automobile business by acquiring J Williams & Co, one of the first dealers for Hindustan Motors in India. Together the four Iranis set up Ideal Jawa India at Yadavagiri (in present-day Karnataka) in 1960, to manufacture the bike in India.

Darukhanawala recalls that by the late ’60s, Indian-made bikes were already popular — Bullet, manufactured by Enfield India, Rajdoot from the Escorts Group, and Jawa from Ideal Jawa. “But the Jawa was perhaps the most popular back then,” Darukhanawala says over a snack of scrumptious chicken sandwiches at his home in Pune.

The bike won a loyal following across a spectrum of users — from milkmen depending on it for their early-morning deliveries and middle-aged men ferrying kids to school to speed junkies raring to burn race tracks. The reason was not far to seek — the Jawa’s well-engineered, yet simple design offered wonderful riding comfort on even the worst of Indian roads.

“Czechoslovakia was also like independent India after World War II — there were shortages, no road infrastructure. So they had to ensure that the product would be able to last long. That’s how it was essentially engineered,” he says.

Old-timers such as Mumbai businessman Kirti Ruparel swear by the Jawa’s “unique personality”. “There were tons of British motorcycles at the time, but the Jawa had a distinctive headlamp nacelle, with the handlebars going through it. Besides, the engine had a ring unlike any other,” he says.

Yvette and Ladislaus Pereira with their Jawa Type 353, which they bought in 1965 for INR 3,000. It continues to sit pretty in their garage these days.

Photo courtesy: Kyle Pereira

Jawa to Yezdi

In the early days of the import, the bike parts arrived in a box and they were assembled locally. To save on cost, the Iranis began making a few of the parts in India, and gradually they were able to manufacture most of them locally. A few of the parts were outsourced to other local manufacturers.

Though they had initially wanted to set up their plant in Pune, they finally settled on Yadavagiri, courtesy Maharaja Jayachamaraja Wadiyar of Mysore. The first Ideal Jawa bike rolled out from the facility in 1961.

The numbers increased steadily, until in 1974 it touched 20,701 bikes. At this point, when the government asked Indian enterprises to create an identity of their own, the Jawa was rechristened Yezdi, in memory of the Iranis’ origins in Yazd (formerly Yezd), Iran.

The collaboration between the Iranis and their Czech counterparts at Jawa blossomed from the start. Darukhanawala writes about how a number of Indian technicians were sent to Czechoslovakia for training in production and factory management: “…the Czech firm was most forthcoming in its sharing of technology and experience and this they would continue to do for the next two decades as well which speaks volumes about the kind of relationship the Iranis fostered via their principled approach”.

In fact, when Iran wanted the Yezdi to be manufactured in that country — given the motorcycle’s connection with Yezd — the Iranis forwarded the request to their Czech partners, instead of dealing with it on their own.

“I had the opportunity to visit the factory on a few occasions in the early ’80s and was impressed by its state-of-the-art technology and scale of manufacturing,” Darukhanawala recalls. The book follows the story of the Jawa in India all the way to the day — May 25, 1996 — the factory shut shop after rolling out the last lot of Yezdis.

Racing days

Making a short detour, Darukhanawala delves into the racing history of the Jawa — both internationally and in India.

He narrates how the Czech ace Franta Stastny came down to participate in local races in Mysore in 1961, and could be spotted riding around town on his ‘double knocker 500cc Jawa Grand Prix bike’. There were also homegrown stars such as Bahirji Shankarrao Shinde, a trusted factory mechanic-turned-race jockey, as also several young members of the Irani household such as Fariborz, Tehmtom, Sheroy and Rustom Hormuzdi.

“Many members of the Irani family were great racers. That is a rather unique thing for a company that owned a brand and also had its progeny into racing,” Darukhanawala says.

From the ’50s to the ’70s, the airports at Lohegaon in Pune and Juhu in Mumbai were at the heart of all the bike racing action, and aficionados spent a great deal of time tinkering with their bikes both at home and at the venues before getting on to the race track.

The racing scene also had a few geniuses such as the Mysore-based Somender Singh. An engineering college dropout, self-taught mechanic and racer, he started a little garage close to the factory. One of his first lessons involved dismantling the Jawa to understand its working. Soon, he was one of the greatest critics of Ideal Jawa machines.

“I was lucky to have witnessed the development of the motorcycle from the day it was first assembled from boxes, until it was completely manufactured in India,” says Singh, now 71. “I would bump into Czech mechanics around town, would learn from Shinde, who lived right across from my home, and would visit bars to meet factory workers, mostly when they had received their bonus,” he says.

Darukhanawala writes, “Easier said than done, but at Sholavaram [racetrack, near Chennai] in 1975, Singh did the impossible and beat Sheroy Irani and Rustom Hormuzdi to mark the first defeat of the invincible Yezdis at the hands of their very own backyard tinkerer!”

“It’s only when the Japanese bikes came into India in the mid-’80s that the Jawas/Yezdis started losing relevance. The technology employed by Ideal Jawa turned ancient in a few years. In their entire history, they made just 5.5 lakh bikes,” he says.

The rebirth

Even after the factory shut shop, the passionate community of riders kept the flame burning. Weekend scouting trips involved visits to spare parts stores, and, whenever something was found available, buying all of it, only to share with those who needed it.

The love spread seamlessly to the next generation of riders. Kyle Pereira grew up watching his father ride a 1965 Jawa 250. Despite the struggle with spares, three more Jawa/Yezdis rolled into the Pereira household.

“When I started touring, it was restricted to rides around Mumbai due to the paucity of spares… also remember it’s an old bike, so riding 400km was like a feat in itself and 70kmph felt like breakneck speed,” he says.

It took a few discussions between Anupam Thareja — founder, Classic Legends, Anand Mahindra — Chairman, Mahindra Group, and Rustom’s son Boman Irani to relaunch the iconic Jawa last year. The bikes will be manufactured in India and have nothing to do with the Jawas in the Czech Republic.

Darukhanawala explains in the book just what went into the creation of the new line and its design philosophy, to take it closer to the older generation of bikes in terms of riding pleasure.

Pereira, who runs a motorcycle restoration business these days, remembers the Jawa to be a working man’s motorcycle, while it was the Enfield Bullet that had the “cool” factor, since it was always being ridden by a cop, sarpanch or politician. But ever since talks of the relaunch cropped up, the Jawas have been in demand.

“Most would splurge on an old British motorcycle. A few years ago, nobody would look at you if you went to a vintage rally on a Jawa. But these days, the demand has increased and the prices have shot up exponentially,” Pereira says, adding that the price of a Road King model in running condition would be around ₹1.3 lakh today.

The book brings to life a time gone by, when Mumbai was Bombay, Pune was Poona, and Mysuru, Mysore. The old names go well with the flow of the story, as it explains how a relatively modest-looking motorcycle captured the imagination of bikers over the years.

Ironically, it wasn’t until three years ago that Darukhanawala bought his first Jawa Type 353 — a rare machine from 1956, which he restored at Bhau Satalkar’s Vishwakarma Garage in Pune.

Having edited a number of magazines in the years in between, he brings to his writing his journalistic flair, managing to strike a chord with the technical geeks and nostalgic souls alike.

Then, of course, there is the narration of a love affair that began with his first photoshoot and continues to this very day.