Jawa aficionados recall the charms of the motorcycle on its return.

First published: https://www.firstpost.com/india/return-of-the-jawa-as-the-iconic-bike-makes-a-comeback-many-fondly-remember-its-heyday-5660411.html

As the iconic bike makes a comeback, many fondly remember its heyday

For those who have memories from the 1960s, two distinct sounds captured the imagination of most while out on Indian roads. One was the “thump” of the Royal Enfield, the sonorous “dug dug dug dug” that demanded attention; the other, the chirpy “ding, di ding ding ding” of the Jawa motorcycle that complemented its elfin exterior.

The Enfield managed to survive the test of time over the years; more so, due to the loyalty of the armed forces and police, and a hearty attempt to relaunch the bike a few decades ago. The Jawa on the other hand, pulled off a vanishing act in the early 70s, before donning another avatar in the form of a Yezdi, but eventually meeting an untimely end in 1996 when the parent company, Ideal Jawa Pvt Ltd, shut shop.

Last week, those who have been knotted in that everlasting love affair with a Jawa made a beeline for Mumbai, where the bike was relaunched after over two decades. It was a mix of curiosity and scepticism, unsure on what technology would have done to their baby. And while opinions on the Jawa and Jawa 42 models were aplenty, what united them was a sense of nostalgia, reminiscing about the good ol’ days of yore.

The origins

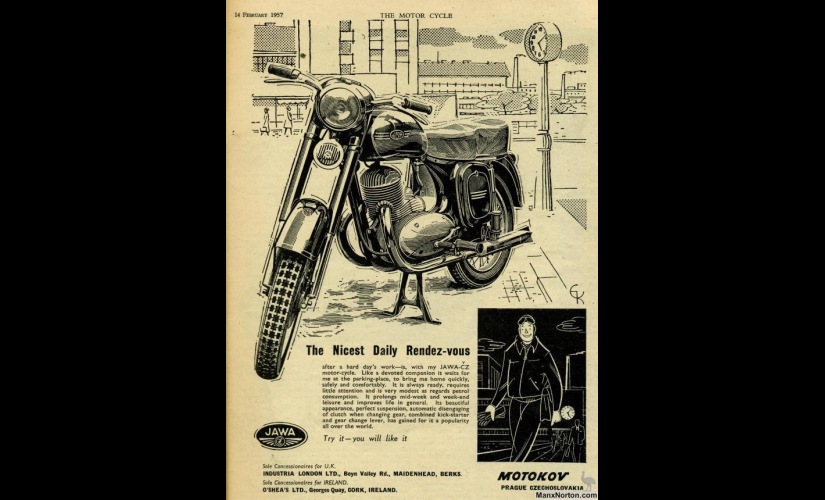

Born in 1929 in what was then Czechoslovakia, the Jawa made its way into India in 1961, courtesy Rustom and Farrokh Irani. Once Ideal Jawa was set up, it was a welcome change from the British bikes that were dominating the Indian market at the time.

For a then princely sum of Rs 3,600, Hiranmoy Chatterjee, 83, remembers moving on from his scooter to a Jawa back in 1964 — the first to ride one at the Rail and Structural Mill at the Bhilai Steel Plant.

“They called it the ‘big, red horse’. Most rode scooters at the time and when I couldn’t cough up the entire sum, I borrowed money to buy a Jawa. The Royal Enfield was still more expensive and had a terrible back kick, so the Jawa was a better bet,” Chatterjee says.

“I would park it at the garage of the superintendent. My immediate boss was still riding a scooter then, so it didn’t go down very well with him,” he chuckles.

One of the longer rides that he undertook was to Nagpur from Bhilai — a distance of about 250 km each way — and the only complaint that Chatterjee remembers having was the wheels.

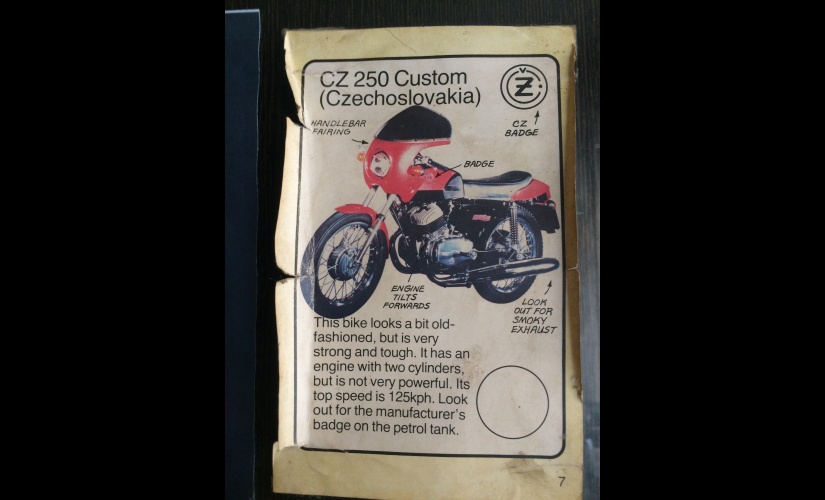

“See, they were Czech made and the treads were not at all suited for Indian roads. The tyres on the Yezdi were much better,” he says.

“But it was a very simple, sturdy machine,” he adds.

There was little in terms of a style statement associated with the bike then. What stood out, however, was the reliability of the machine, with few breakdowns even on long rides, besides its ease of manoeuvring and sprightly persona.

Homemade

The Iranis soon reduced dependancy on the imports by starting to manufacture Jawas at their facility in Mysuru. Boman Irani, Rustom’s son, who has been instrumental in the relaunch, remembers his first walk in the factory as a seven-year-old.

“I was in awe of the setup and asked all kinds of questions to the “uncles” working there. It was only when I was studying engineering at Saboo Siddik and learned about the process, did I realise the level of my father’s involvement in the daily running of the factory,” Irani says.

In the next few years, Irani was riding a Jawa on the sly, given that his feet just about touched the ground. And by the time he was in his teens, he had set out on the rallying and dirt track circuit around Mysuru on an imported Jawa Scrambler. The Jawa was not only a favourite with commuters, but also had its own fan following in the racing community across Mysuru, Pune, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Kolkata.

“It had great acceleration and a fabulous sweep when you went into a corner, besides being really sturdy. It also had good low-end torque and a grunt to it — a genuine workhorse and absolute value for money. You must remember that owning a bike then wasn’t about lifestyle for most — it was simply something that you used for commuting,” Irani says.

Birth of Yezdis

Once the collaboration between the Iranis and Jawa ended in the early 70s, Ideal Jawa got busy with the marketing of their own baby, the Yezdi. And it wasn’t much different from a Jawa.

“It was the same machine on the inside when you look at the first Yezdi, the type ‘B’. Only the fuel tank and engine cover became rectangular, instead of circular. The size of the silencer and the quality of the material was also the same, so the firing was just like a Jawa’s. Most people knew it was the same bike, so sales were hardly affected,” says Aspi Khansaheb, 62, a mechanic who was employed at Ideal Jawa and has been servicing Yezdis since the early 80s.

“And by then, there were more Yezdis than Enfields,” he adds.

The Yezdis captured the imagination of riding enthusiasts around the country and developed a cult following thanks to Bollywood movies such as Humjoli, Parvarish and Chasme Buddoor. One of the favourite dinner table conversations at the Chaubals is how the Yezdi came home.

“I asked my father why he didn’t buy an Enfield. He says that whenever he saw a movie, he always saw a cop on an Enfield, while he chased a thief who was on a Yezdi. And that really appealed to him,” says Akshay Chaubal, a second generation rider.

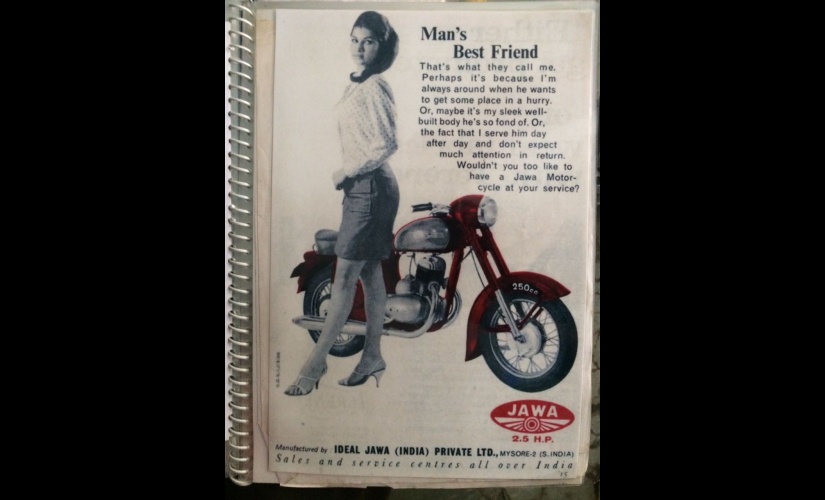

The charms of the bike were further sold through the success of cricketer Ravi Shastri, the Yezdi 250 branded as “The Champ’s Choice”, while another tongue-in-cheek ad featuring a pretty lass and a Jawa announced, “Man’s Best Friend” for “my sleek well-built body he’s so fond of” or “the fact that I serve him day after day and don’t expect much attention in return”.

During a brief, two-month stint at a garage in Bandra, Khansaheb remembers the bike captivating a young Sanjay Dutt, who would make it a point to visit the workshop during his jaunts at Bandstand.

“He would ask for a round or two. He was still young then and so was I, so we hit it off,” he recalls.

Reliable mate

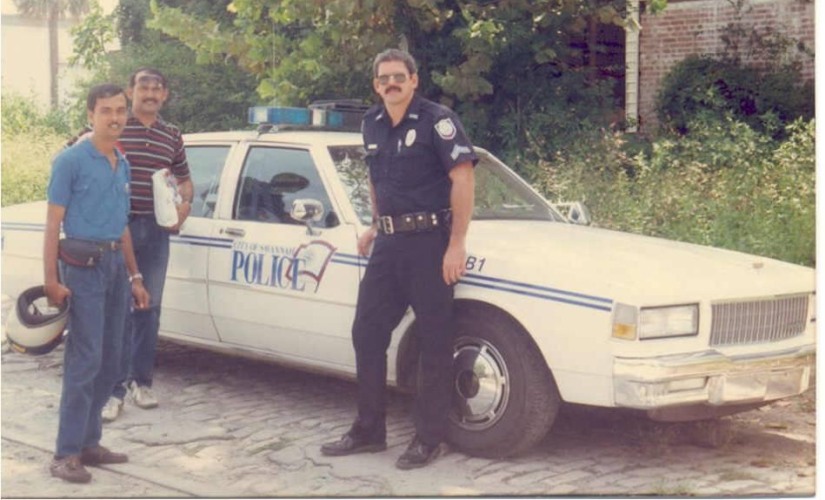

The bike was also exported to countries such as Australia, Turkey and the Middle East, with a few models such as the Yezdi Dollar Roadking manufactured only for export and could be bought in India if one had the “dollars”. While it soon earned the repute of being a reliable touring bike in India, a few like the trio of Arun Khadse, Satish Ganpati and Stanley Francis Rose even took it to foreign shores — first to the United States and then to Australia.

“We used to regularly ride to Shirdi after work when at Tata Power in Mumbai, which soon progressed to longer trips down south. You hardly ever saw a Jawa or Yezdi stranded on the road,” he says.

“It was then that we planned a ride in the US, and finally set off in 1990, after the two bikes had been shipped a month in advance,” Khadse says.

The first hurdle was at New York, when the officer had an issue with the two-stroke bikes and if they were suited to the stringent pollution norms. But after persisting for a week, he finally relented and handed them a three-month permit. “To pollute the United States,” Khadse laughs.

The first few days came as a shocker, especially on the multi-lane American freeways. Riding in the last lane, which is usually the domain of 18-wheeler trailers, the featherweight bikes were quite literally blown off the road with each passing. When they decided to move on to smaller roads, their rides drew a lot of curious stares en route.

“Those were times when folks toured on bikes over 1000 cc, so they couldn’t quite believe that it was possible to ride hundreds of miles on these small ones. Our bikes were christened “The Indian Babies” and made a lot of headlines wherever we went,” Khadse recalls.

During the 18,400 km ride spanning 32 states, the three even encountered a thunderstorm, which quite literally knocked the wind out of them while riding in a heavy downpour. The bikes though showed no signs of slowing down and cruised through the storm.

End of an era

When Rustom Irani passed away in 1989, Ideal Jawa was in desperate need of a leader to continue the good work. But when that turned out to be a tough ask, the company closed down in 1996.

“It was the saddest day of our lives. Over the next few years, I made repeated attempts to bring alive the brand. But eventually, it happened when it had to,” Irani says.

Those with Jawas had it easy when it came to finding spares for the first few years. But as newer brands entered the market, it became increasingly harder and the Yezdis too gradually started shying away from Indian roads.

“A few mechanics moved on to other bikes, but since I had worked with Jawas and Yezdis all my life, I continued repairing the bikes that came my way. Around 2001-02, business was really down,” Khansaheb says.

The resurgence

A few sold their Jawas and Yezdis, others let it stay on as a dead asset in their parking lots. That, in turn, was a boon for enterprising teenagers, who looked to get their first bike with their measly salaries when just out of college. And didn’t mind getting their hands dirty.

“I bought my first Jawa in 2000 from a local garage. I had a choice between a Hero Honda and a Jawa. Luckily for me, my mother used to go to college on a BSA Bantam 125, and she was quite clear it had to be a Jawa,” Amresh Sawant says, smiling.

The lucky few like Chaubal had the choice of restoring a dormant one lying in the garage, after pestering his dad for a new bike, and soon had an identity of his own at college, thanks to his vintage ride. Others such as Aniket Shirkar made a quick buy at the then throwaway prices for sentimental reasons.

Back in the day, spotting another Jawa on the road called for a chase until the next signal, whereafter catching up, a conversation and camaraderie ensued. But once the internet was accessible for most, the advent of messenger groups slowly rounded up a community, that shared everything from handy tips on maintenance, spare parts and eventually, long rides.

“The Yezdi Jawa Owners Club of India was started in August 2000. The community is really tight, because everybody needs somebody at some point of time for spares,” Sawant says.

Anyone who was visiting the Czech Republic was expected to bring back a bag full of parts, since it was still being manufactured there. The news of an old shop of spare parts shutting down called for a quick raid to hoard any component that could be of use later.

“In fact, for a brief period after the factory closed, Ideal Jawa were still selling assembled bikes, which could be registered through dealers in Bengaluru and Mysuru. Later, they auctioned off parts to a scrapyard in Palus near Karad. You could go buy spares by the kilo, starting out as low as Rs 12/kg — engines, chassis, silencers, anything that you needed,” says Alok Balsekar.

Once social networking sites came up, the community got even stronger and starting marking out mechanics and support groups on online maps that could be of use to anyone who was touring around the country. Irani too set up a website to bring the community together and keep the brand alive in the mind of the faithful.

Jawa returns

The relaunch this month brought the Jawa, as well as the many memories associated with it, back to life and Irani swears that they have paid complete attention to the engineering to see that it rides as close as possible to the original.

“It tugs at your hearts strings and at the same time, makes for absolute riding pleasure when you are in the city and you have to wean through traffic because it has such a beautiful, low centre of gravity, which kind of helps you flip the bike around. And then if you are on the highway at 125-130 kmph, it’s like you are on rails — that steady,” he says.

Those in tune with the bike couldn’t agree more after the first look — from the original colour, the “Jawa red”, to the firing of the engine.

“I’ve heard that they took a lot of efforts to make the bike sound the same. They had different sets of silencers made and even hired a sound engineer for this,” Balsekar says.

Rest assured, the “ding, di ding ding ding” is only set to get louder in the days to come.