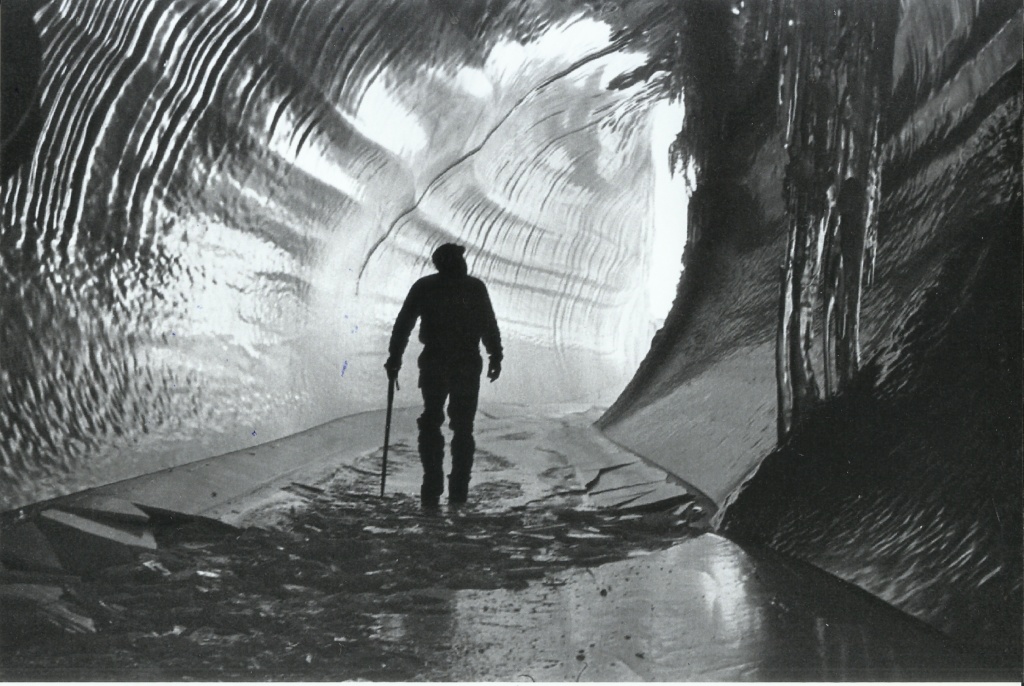

Narinder ‘Bull’ Kumar explored places that few visited during his mountaineering days. One such exploration took him to the Siachen.

Remembering Narinder ‘Bull’ Kumar, one of India’s greatest mountaineers

Narinder Kumar, who passed away recently, built up a legendary reputation as a mountaineer and a Himalayan explorer

As a school boy, Narinder ‘Bull’ Kumar once decided to ride a bicycle to Tibet alongside his boy scout buddies. In their bags, they had packed groundnuts and jaggery to see them through the journey, apart from puncture kits to tackle the rough terrain ahead.

It was evident that they wouldn’t get very far from their school in Shimla. But for Kumar, this was the start of a life of adventure that would eventually lead him to many firsts on the big mountains in the Himalaya. With his death on 31 December at the age of 87, the world of mountaineering has lost a pioneer, who will be best remembered back home for staking India’s claim to the Siachen glacier.

Kumar was born in Rawalpindi in undivided India in 1933, and a year before India’s independence, moved to Shimla where his father was headmaster at the Government High School. In fact, he was away on a World Scout Jamboree in France during the partition, oblivious to the havoc unfolding back home just like the other teenagers who had accompanied him.

“I remember there was a Sardarji with a green pagdi and we made a Pakistan flag out of it to celebrate independence day. We only realised what had happened when all the ‘Pakistani’ boys were sent to Karachi while we came back to Bombay (now Mumbai),” Kumar recalled during an interaction in November last year.

It was after joining the Indian army as part of the Kumaon Regiment that Kumar earned the moniker ‘Bull’ for his tenacity in the boxing ring. Things were no different on the mountains. As a climber and a leader, Kumar went from strength to strength, beginning with the ascent of Trisul in the Kumaon Himalaya in 1958. Two years later, while climbing Everest, Kumar and his climbing partner Sonam Gyatso had to abandon the summit attempt just a few hundred metres shy of the top, due to frozen oxygen masks and bad weather. He battled the elements again on Neelkanth in 1961, surviving a harrowing descent and frostbite that resulted in his toes getting amputated.

“I rarely put myself on the summit during most expeditions because someone had to ferry the loads and open the routes. This would ensure that the summit party was in the best shape to make it to the top,” Kumar said.

The success of the Neelkanth climb was later questioned by Jagdish Nanavati of the Himalayan Club, who found a number of discrepancies in the expedition report. Kumar took a few months to recover from his injuries, but was soon back in the mountains. He started donning battery heated socks to keep his feet warm and in 1964, led the first successful Indian attempt on Nanda Devi in the Garhwal Himalaya. The next year, he was deputy leader of the Indian team that finally reached the top of Everest, smashing many records along the way. Kumar was awarded the Padma Shri in 1965 for this feat.

“Though he was listed as being in the ‘medical category’ in army parlance, and was not supposed to go over 8,000 ft., he spent most of his life above that height! No wonder he went by the nickname ‘Bull’ for the remarkable strength he had shown as Deputy Leader of the Indian team to Everest in 1965. A jolly fellow, as the army would call him, he had served as the principal of the (Himalayan) mountaineering institute where his favourite fun-trick was to show his toe-less feet to horrified women students and charge them ₹1 each!” writes legendary mountaineer and Piolets D’Or awardee Harish Kapadia in his book Siachen Glacier: The Battle of Roses.

Kumar’s finest hour came in 1977 when he led the team that made the first ascent of Kangchenjunga via the unclimbed north-east spur. It was a route that had defeated two German expeditions led by Paul Bauer in 1929 and 1931. Though the British succeeded in making the first ascent of the world’s third-highest peak in 1955 via the north-west face, the unclimbed north-east spur posed a formidable challenge, until Prem Chand and Nima Dorji reached the top on the evening of 31 May.

“While we did succeed, it was unfortunate to lose one team member, Sukhvinder Singh. We gave him a proper burial and I then consulted the team, before arriving at the decision to continue with the climb,” Kumar said. “In fact, my brother Kiran was at the last camp and ready to go for the summit (as part of the second team). But I had to call him down because the impending monsoon would make conditions difficult on the mountain. He never forgave me for that,” he added.

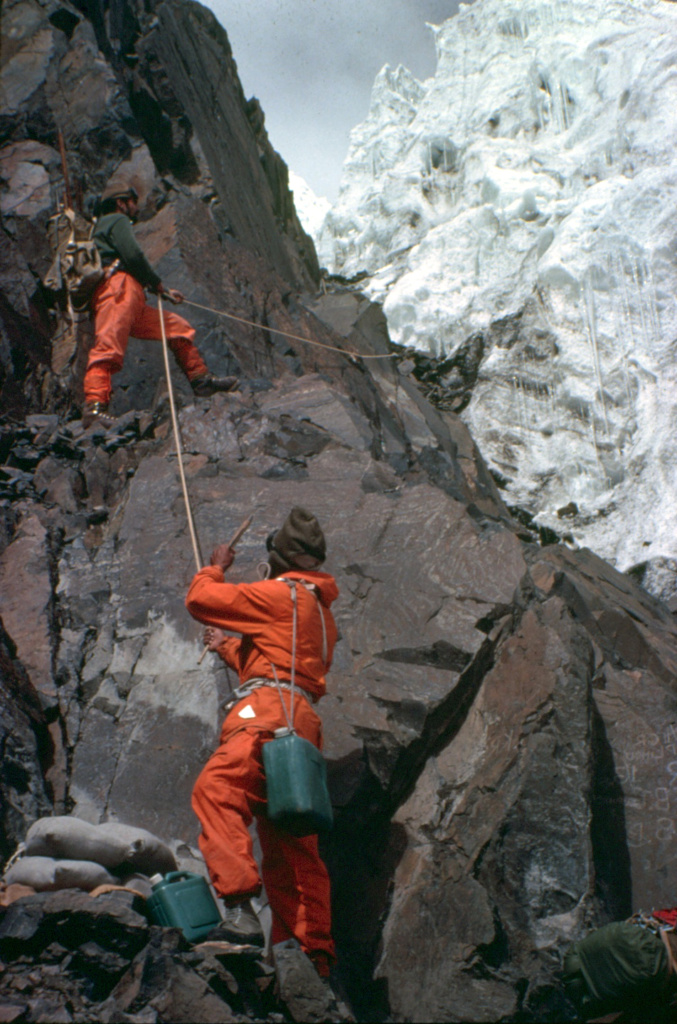

While seeking his next mountaineering objective, he stumbled upon a map of the Siachen Glacier brought to him by a German friend. Inspecting it, Kumar realised that there was a cartographic error when it came to marking the Line of Control as claimed by Pakistan, which put an area of over 5,000 square kilometre in the Pakistan-claimed territory. Kumar set off on a secret mission with a team from the High Altitude Warfare School where he was director. The objective was to climb a peak, Teram Kangri II, that lies on the main crest of the Great Karakoram range, to highlight India’s presence on the glacier.

“It was a politically important event. The soldier mountaineers were standing in the Shaksgam valley – one of the most inaccessible regions of the world, that not more than a handful of people had dared to enter. That was the region that Pakistan had ceded to China in 1963, even though the area belonged to India,” Kumar wrote in his memoir Soldier Mountaineer.

In 1981, he returned as part of a large-scale expedition to pull off a traverse of the Siachen Glacier, climbing to strategic passes like Bilafond La, Turkestan La and Indira Col, as well as peaks such as Sia Kangri I and Saltoro Kangri I. For his invaluable contribution to reconnaissance, he was awarded the MacGregor Memorial Medal by the United Service Institution of India.

“I reached the summit only once in my later years, which was on Sia Kangri. I was at the last camp and when the team came back, I realised they had not climbed it. So the next day, I went up and realised they were around 700 feet short. I then took the flag to the top,” Kumar said.

By 1984, when Kumar was finding his feet with his commercial enterprise that promoted mountaineering and trekking, the first of the battles for Siachen had begun between India and Pakistan. Chewang Motup, a mountaineer and president of the Himalayan Club, who worked for Kumar’s outfit in the late 80s, remembers leading a joint Indo-American expedition to Sia Kangri in 1986.

“The Americans were issued a permit to climb the mountain by Indian authorities to highlight that it was part of Indian territory. To scare us, the Pakistanis started shelling since they didn’t want us to succeed. We didn’t want to risk it, so an Indian army team climbed Sia Kangri while I led the Americans to Indira Col and Turkestan La,” Motup recalls. Motup says that the expedition was Kumar’s idea. “Given his networks, it was his idea that nationals of Pakistan’s main ally, the United States, should climb Sia Kangri from India. It made a big statement to the world. I believe his expeditions were very important for India—had he not gone things would well have been different today,” he adds.

In 1990, Motup remembers visiting Sikkim with Kumar to showcase rafting on the Teesta river. Despite the ‘big waves and rapids’, Kumar, now nearing his 60s, insisted that he wanted to be on the two-man catamaran.

“He’s left a big footprint on the Indian mountaineering and adventure scene. He was always ahead of his time, wanting to do things that hadn’t been done before,” Motup says.

During our meeting a couple of months ago, it was evident that Kumar wasn’t in the best of health. But his booming voice was still in evidence, reminiscent of the time he called the shots as one of India’s greatest Himalayan climbers.